What was the Age of Enlightenment/ Age of Reason and what led to this shift in thought

Assessment | Biopsychology | Comparative | Cerebral | Developmental | Language | Private differences | Personality | Philosophy | Social |

Methods | Statistics | Clinical | Educational | Industrial | Professional person items | World psychology |

Philosophy Alphabetize: Aesthetics · Epistemology · Ethics · Logic · Metaphysics · Consciousness · Philosophy of Language · Philosophy of Mind · Philosophy of Science · Social and Political philosophy · Philosophies · Philosophers · List of lists

Delight help to improve this folio yourself if you can..

The Age of Enlightenment refers to the 18th century in European philosophy, and is often thought of as part of a larger period which includes the Age of Reason. The term also more specifically refers to a historical intellectual movement, "The Enlightenment." This movement advocated rationality as a means to constitute an authoritative system of ethics, aesthetics, and cognition. The intellectual leaders of this move regarded themselves as courageous and elite, and regarded their purpose as leading the earth toward progress and out of a long period of doubtful tradition, full of irrationality, superstition, and tyranny (which they believed began during a historical period they chosen the "Night Ages"). This movement too provided a framework for the American and French Revolutions, the Latin American independence movement, and the Shine Constitution of May 3, and also led to the rising of commercialism and the nativity of socialism. It is matched by the high baroque and classical eras in music, and the neo-classical menstruation in the arts, and receives contemporary awarding in the unity of science movement which includes logical positivism.

Another important motility in 18th century philosophy, which was closely related to it, was characterized by a focus on belief and piety. Some of its proponents attempted to employ rationalism to demonstrate the existence of a supreme being. In this menstruation, piety and belief were integral parts in the exploration of natural philosophy and ethics in addition to political theories of the age. Nevertheless, prominent Enlightenment philosophers such every bit Voltaire, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and David Hume questioned and attacked the existing institutions of both Church and State.The 18th century also saw a continued ascension of empirical philosophical ideas, and their application to political economy, regime and sciences such as physics, chemical science and biology.

According to scholarly stance[How to reference and link to summary or text], the Enlightenment was preceded by the Age of Reason (if thought of as a brusk catamenia) or by the Renaissance and the Reformation (if thought of as a long flow). It was followed by Romanticism.

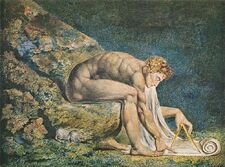

William Blake's Newton equally a divine geometer (1795)

History of Enlightenment philosophy

The boundaries of the Enlightenment cover much of the 17th century as well, though others term the previous era "The Age of Reason." For the present purposes, these two eras are separate; however, it is equally acceptable to call back of them conjoined as one long period.

Throughout the 1500s and half of the 1600s, Europe was ravaged past religious wars. When the political situation stabilized afterward the Peace of Westphalia and at the end of the English language Ceremonious War, there was an upheaval which overturned the notions of mysticism and religion in private revelation as the main source of knowledge and wisdom—perceived to have been a driving strength for instability. Instead, (according to those that split the two periods), the Age of Reason sought to establish axiomatic philosophy and absolutism every bit the foundations for knowledge and stability. Epistemology, in the writings of Michel de Montaigne and René Descartes, was based on extreme skepticism, and inquiry into the nature of "noesis." This goal in the Age of Reason, which was built on self-evident axioms, reached its superlative with Baruch (Benedictus de) Spinoza's Ethics, which expounded a pantheistic view of the universe where God and Nature were one. This idea became cardinal to the Enlightenment from Newton through to Jefferson.

The Enlightenment was, in many ways, influenced by the ideas of Pascal, Leibniz, Galileo and other philosophers of the previous period. For instance, E. Cassirer has asserted that Leibniz's treatise On Wisdom ". . . identified the central concept of the Enlightenment and sketched its theoretical plan" (Cassirer 1979: 121–123). There was a wave of change across European thinking at this fourth dimension, which is also exemplified by the natural philosophy of Sir Isaac Newton. The ideas of Newton, which combined the mathematics of axiomatic proof with the mechanics of physical observation, resulted in a coherent system of verifiable predictions and set the tone for much of what would follow in the century later on the publication of his Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica.

Merely Newton was not alone in the systematic revolution in thinking; he was merely the most visible and famous example. The idea of compatible laws for natural phenomena mirrored the greater systematization in a variety of studies. If the previous era was the historic period of reasoning from kickoff principles, Enlightenment thinkers saw themselves as looking into the listen of God by studying creation and deducing the bones truths of the earth. This view may seem overreaching to some in the present-day, where conventionalities is that human beings apprehend a truth that is more provisional, but in that era it was a powerful notion which turned on its head the previous basic notions of the sources of legitimacy.

For those that divide the "Age of Reason" from the "Enlightenment," the precipitating figure of Newton offers a specific example of the importance of the difference, because he took empirically observed and codified facts, such as Kepler'due south planetary motion, and the "opticks" which had explained lenses, and began to create an underlying theory of how they functioned. This shift united the pure empiricism of Renaissance figures such as Sir Francis Bacon with the evident approach of Descartes. The conventionalities in a comprehensible earth, under an orderly Christian God, provided much of the impetus for philosophical enquiry. On the one paw, religious philosophy focused on the importance of piety, and the majesty and mystery of God's ultimate nature; on the other hand, ideas such as Deism stressed that the globe was attainable to the kinesthesia of human reason, and that the "laws" which governed its behavior were understandable. The notion of a "clockwork god" or "god the watchmaker" became prevalent, as many in the time menstruation saw new and increasingly sophisticated machines as a powerful metaphor for a seemingly orderly universe.

Cardinal to this philosophical tradition was the belief in objective truth independent of the observer, expressible in rigorous human terms. The quest for the expression of this truth would atomic number 82 to a serial of philosophical works which alternately advanced the scepticist position that information technology is impossible to know reality in the realm of experience, and the idealist position that the heed was capable of encompassing a reality which lies outside of its straight experience. The human relationship between existence and perception would exist explored by George Berkeley and David Hume, and would eventually be the problem that occupied much of Immanuel Kant's philosophy.

The focus on law, involving the separation of rules from the particulars of behavior or feel, was essential to the rise of a philosophy which had a much stronger concept of the individual; according to this concept, his rights were based on ideals other than aboriginal traditions, or tenures, and instead reflected the intrinsic quality of a person as defined by the philosophers of the historic period. John Locke wrote his 2 Treatises on Authorities to argue that property was not a family right by tenure, just an individual right brought on past mixing labour with the object in question, and securing information technology from other use. This focus on process and procedure would be honoured, at times, in the breach, as England'southward own "Star Sleeping room" courtroom would attest to. Nevertheless, once the concept established that there were natural rights, equally there were natural laws, information technology became the ground for the exploration of what we would now call economic science, and political philosophy.

In his famous 1784 essay "What Is Enlightenment?", Immanuel Kant defined it as follows:

Enlightenment is man's leaving his self-acquired immaturity. Immaturity is the incapacity to employ one's intelligence without the guidance of some other. Such immaturity is self-caused if it is non caused by lack of intelligence, simply by lack of determination and courage to employ one'southward intelligence without existence guided by another. Sapere Aude! [Dare to know!] Take the courage to use your own intelligence! is therefore the motto of the enlightenment.

The Enlightenment began then, from the conventionalities in a rational, orderly and comprehensible universe—then proceeded, in stages, to form a rational and orderly organization of knowledge and the country, such as what is found in the idea of Deism. This began from the assertion that constabulary governed both heavenly and human affairs, and that constabulary invested the king with his power, rather than the rex's power giving force to police. The formulation of police as a relationship betwixt individuals, rather than families, came to the fore, and with it the increasing focus on individual liberty as a central right of man, given by "Nature and Nature's God," which, in the ideal state, would embrace as many people as possible. Thus The Enlightenment extolled the ideals of liberty, property and rationality which are nonetheless recognizable as the ground for most political philosophies even in the present era; that is, of a free individual beingness mostly free within the dominion of the country whose function is to provide stability to those natural laws.

The "long" Enlightenment is seen as beginning the Renaissance drive for humanism and empiricism. Information technology was built on the growing natural philosophy that espoused the awarding of algebra to the study of nature, and the discoveries brought almost by the invention of the microscope and the telescope. There was besides an increasingly complex philosophy of the role of the state and its relationship to the individual. The turbulence of religious wars had brought most a desire for remainder, order, and unity.

Two practiced examples which help illustrate why many historians split the Age of Reason from the Enlightenment are the works of Thomas Hobbes and John Locke. Hobbes, whose ideas are a production of the age of reason, systematically pursues and categorizes human emotion, and argues for the need of a rigid organisation to hold back the chaos of nature in his piece of work Leviathan. While John Locke is clearly an intellectual descendant of Hobbes, for him the state of nature is the source of all rights and unity, and the state's role is to protect, and not to concur back, the state of nature. This primal shift, from a rather chaotic and dark view of nature, to a fundamentally orderly view, is an of import aspect of the Enlightenment.

A 2nd moving ridge of Enlightenment thinking began in French republic with the Encyclopédistes. The premise of their enterprise was that there is a moral architecture to knowledge. Mixing personal comment with the attempt to codify knowledge, Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d'Alembert sought liberation for the listen in the power to grasp cognition.

The Enlightenment was suffused with two competing strains. 1 was characterised by an intense spirituality, and faith in organized religion and the church building. In opposition to this, there was a growing streak of anti-clericalism which mocked the perceived distance between the supposed ideals of the church, and the practice of priests. For Voltaire «Écrasez 50'infâme! » ("Crush Infamy!") would be a boxing cry for the ideal of a triumphant, rational club.

By the mid-century, what was regarded by many as the pinnacle of purely Enlightenment thinking was being reached with Voltaire—whose combination of wit, insight, and anger made him the most hailed man of letters since Erasmus. Born François Marie Arouet in 1694, he was exiled to England between 1726 and 1729, and there he studied Locke, Newton, and the English language Monarchy. Voltaire'southward ethos was that "Those who can brand you believe absurdities can brand you lot commit atrocities"—that if people believed in what is unreasonable, they volition do what is unreasonable.

This betoken is, maybe, the central point of contention over the Enlightenment: whether the construction of reason and credibility creates, inherently, as many problems as it deals with. From the perspective of many crucial figures of the Enlightenment, apparent reports, viewed through the lens of reason annealed knowledge, empirical observation, and knowledge should exist compiled into a source which stood as the authoritative one. The opposing view, which was held with increasing force by the Romantic motility and its adherents, is that this process is inherently corrupted by social convention, and bars truth which is unique, individual and immanent from beingness expressed.

The Enlightenment balanced then, on the call for "natural" freedom which was good, without a "license" which would, in their view, degenerate. Thus the Age of Enlightenment sought reform of the Monarchy by laws which were in the best interest of its subjects, and the "enlightened" ordering of guild. The idea of enlightened ordering was reflected in the sciences by, for instance, Carolus Linnaeus' categorization of biological science.

In mid-century Germany, the idea of philosophy as a critical discipline began with the work of Gotthold Ephraim Lessing and Johann Gottfried Herder. Both argued that formal unities that underlie language and structure hold deeper meaning than a surface reading, and that philosophy could be a tool for improving the virtue, political and personal, of the individual. This strain of thinking would influence Kant's critiques, as well as subsequent philosophers seeking an apparatus to examine works, beliefs and social organization, and it is especially notable in the history of later German philosophy.

These ideas became volatile when it reached the bespeak where the idea that natural liberty was more self-ordering than hierarchy, since bureaucracy was the social reality. As that social reality repeatedly disappointed the fundamentally optimistic ideal that reform could end disasters, at that place became a progressively more than strident naturalism which would, eventually, pb to the Romantic move.

Thinkers of the final wave of the Enlightenment—Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Immanuel Kant every bit well as Adam Smith, Thomas Jefferson and the immature Johann Wolfgang von Goethe adopted the increasingly used biological metaphor of cocky-system and evolutionary forces. This represented the impending end of the Enlightenment: which believed that nature, while basically good, was not basically self-ordering—see Voltaire'southward Candide for an example of why not. Instead, it had to be ordered with reasoning and maturity. The impending Romantic view saw the universe every bit self-ordering, and that chaos was, in a existent sense, the result of excesses of rational impositions on an organic world.

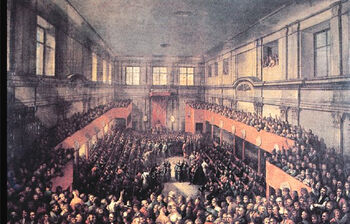

In 1791, the "Great" or Iv-Twelvemonth Sejm of 1788–1792 adopts the May third Constitution at Warsaw'southward Purple Castle.

This boundary would produce political results: with increasing force in the 1750s there would exist attempts in England, Austria, Prussia, Poland and France to "rationalize" the monarchical system and its laws. When this failed to cease wars, there was an increasing bulldoze for revolution or dramatic alteration. The Enlightenment thought of rationality as a guiding force for authorities found its way to the heart of the American Declaration of Independence, and the Jacobin program of the French Revolution, as well every bit the American Constitution of 1787 and the Shine Constitution of May 3, 1791.

The French Revolution, in detail, represented the Enlightenment philosophy through a fierce and messianic lens, specially during the brief menses of Jacobin dictatorship. The desire for rationality in government led to the endeavor to finish the Roman Catholic Church, and indeed Christianity in France, in add-on to changing the calendar, clock, measuring arrangement, monetary system and legal system into something orderly and rational. It also took the ethics of social and economical equality further than any other major state to that time.

But with Napoleon the Enlightenment and its mode breathed its last, and longest breath. Napoleon reorganized French republic into departments, and funded a host of projects. Ane case of the Enlightenment at work in Revolutionary and Imperial France was the metric system. In a uniform organisation of weights and measures, based on evident units—the radius of the world, the weight and thermodynamic properties of water—prices would float based on measurable quantities, rather than price being fixed. It was thought that this would liberate industry from the tyranny of old production laws, and hence from Medieval structure.

Primal conflicts within Enlightenment-menses philosophy

As with most periods, the individuals present within the Enlightenment were more than enlightened of their differences than their similarities; within the period there were schools of thought, which saw themselves equally widely divergent, even equally after perspective has come to consider them similar.

One key disharmonize is on the role of theology - during the previous period, there had been the splintering of the Catholic Church, not, as with previous schisms, largely forth political control of the papacy, merely along doctrinal lines between Roman Cosmic and Protestant theologies. Consequently, theology itself became a source of partisan debate, with different schools attempting to create rationales for their viewpoints, which then, in turn, became generally used. Thus philosophers such as Spinoza searched for a metaphysics of ethics. This trend would influence pietism and eventually transcendental searches such equally those past Immanuel Kant.

Religion was linked to some other feature which produced a cracking deal of Enlightenment thought, namely the rise of the Nation Country. In medieval and Renaissance periods, the state was restricted past the demand to work through a host of intermediaries. This system existed because of poor communication, where localism thrived in return for loyalty to some central organization. With the improvements in transportation, arrangement, navigation and finally the influx of gilt and silver from trade and conquest, the state began to assume more than and more authority and power. The response against this was a series of theories on the purpose of, and limits of country power. The Enlightenment saw both the cementing of authoritarianism and counter-reaction of limitation advocated by a string of philosophers from John Locke frontward, who influenced both Voltaire and Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

Inside the flow of the Enlightenment, these issues began to be explored in the question of what constituted the proper relationship of the denizen to the monarch or the state. The idea that society is a contract betwixt individual and some larger entity, whether club or state, continued to grow throughout this period. A series of philosophers, including Rousseau, Montesquieu, Hume and ultimately Jefferson advocated this thought. Furthermore, thinkers of this age advocated the thought that nationality had a ground beyond mere preference. Philosophers such as Johann Gottfried von Herder reasserted the idea from Greek antiquity that language had a decisive influence on noesis and thought, and that the significant of a particular volume or text was open to deeper exploration based on deeper connections, an idea now called hermeneutics. The original focus of his scholarship was to delve into the pregnant in the Bible and in order to proceeds a deeper agreement of it. These two concepts - of the contractual nature between the state and the citizen, and the reality of the "nation" beyond that contract, had a decisive influence in the evolution of liberalism, democracy and constitutional government which followed.

At the same time, the integration of algebraic thinking, acquired from the Islamic world over the previous two centuries, and geometric thinking which had dominated Western mathematics and philosophy since at least Eudoxus, precipitated a scientific and mathematical revolution. Sir Isaac Newton's greatest merits to prominence came from a systematic application of algebra to geometry, and synthesizing a workable calculus which was applicable to scientific problems. The Enlightenment was a time when the solar system was truly "discovered": with the accurate adding of orbits, such as Halley'southward comet, the discovery of the first planet since antiquity, Uranus by William Herschel, and the adding of the mass of the Sunday using Newton'due south theory of universal gravitation. The result that this series of discoveries had on both businesslike commerce and philosophy was momentous. The excitement of creating a new and orderly vision of the globe, too as the need for a philosophy of science which could embrace the new discoveries would testify its central influence in both religious and secular ideas. If Newton could order the cosmos with "natural philosophy," and so, many argued, could political philosophy society the trunk politic.

Inside the Enlightenment there were two main theories contending to be the basis of that ordering: "divine correct" and "natural police force." It might seem that divine right would yield absolutist ideas, and that natural law would lead to theories of liberty. The writing of Jacques-Benigne Bossuet (1627-1704) set the prototype for the divine correct: that the universe was ordered by a reasonable God, and therefore his representative on earth had the powers of that God. The orderliness of the creation was seen as proof of God; therefore it was a proof of the power of monarchy. Natural law, began, not as a reaction against divinity, only instead, as an abstraction: God did not rule arbitrarily, but through natural laws that he enacted on earth. Thomas Hobbes, though an absolutist in government, drew this argument in Leviathan. In one case the concept of natural constabulary was invoked, however, it took on a life of its ain. If natural police could exist used to bolster the position of the monarchy, it could too be used to affirm the rights of subjects of that monarch, that if there were natural laws, then there were natural rights associated with them, just as there are rights under man-fabricated laws.

What both theories had in common, nevertheless, was the need for an orderly and comprehensible role of government. The "Enlightened Despotism" of, for instance, Catherine the Cracking of Russian federation is non based on mystical appeals to potency, but on the pragmatic invocation of land power as necessary to hold dorsum chaotic and anarchic warfare and rebellion. Regularization and standardization were seen equally expert things considering they immune the state to reach its power outwards over the entirety of its domain and considering they liberated people from being entangled in countless local custom. Additionally, they expanded the sphere of economic and social action.

Thus rationalization, standardization and the search for fundamental unities occupied much of the Enlightenment and its arguments over proper methodology and nature of agreement. The culminating efforts of the Enlightenment: for example the economics of Adam Smith, the physical chemistry of Antoine Lavoisier, the thought of evolution pursued by Goethe, the proclamation past Jefferson of "inalienable" rights, in the terminate overshadowed the idea of "divine right" and directly alteration of the world by the paw of God. It was as well the basis for overthrowing the idea of a completely rational and comprehensible universe, and led, in turn, to the metaphysics of Hegel and the search for the emotional truth of Romanticism.

Part of the Enlightenment in afterwards philosophy

The Enlightenment occupies a central role in the justification for the movement known as modernism. The neo-classicizing trend in modernism came to come across itself as existence a menstruation of rationality which was overturning heedlessly established traditions, and therefore analogized itself to the Encyclopediasts and other philosophes. A multifariousness of 20th century movements, including liberalism and neo-classicism traced their intellectual heritage dorsum to the "reasonable" past, and away from the "emotionalism" of the 19th century. Geometric order, rigor and reductionism were seen as virtues of the Enlightenment. The mod movement points to reductionism and rationality equally crucial aspects of Enlightenment thinking of which it is the inheritor, as opposed to irrationality and emotionalism. In this view, the Enlightenment represents the basis for modern ideas of liberalism confronting superstition and intolerance. Influential philosophers who have held this view are Jürgen Habermas and Isaiah Berlin.

This view asserts that the Enlightenment was the point where Europe broke through what historian Peter Gay calls "the sacred circle," where previous dogma circumscribed thinking. The Enlightenment is held, in this view, to be the source of critical ideas, such as the axis of freedom, democracy and reason as existence the primary values of a society. This view argues that the institution of a contractual ground of rights would lead to the market mechanism and commercialism, the scientific method, religious and racial tolerance, and the organization of states into cocky-governing republics through democratic means. In this view, the tendency of the philosophes in particular to utilize rationality to every trouble is considered to be the essential alter. From this point on, thinkers and writers were held to be free to pursue the truth in whatsoever form, without the threat of sanction for violating established ideas.

With the end of the Second Globe War and the rising of mail service-modernity, these aforementioned features came to exist regarded every bit liabilities - excessive specialization, failure to heed traditional wisdom or provide for unintended consequences, and the "romanticization" of Enlightenment figures - such as the Founding Fathers of the United States, prompted a backlash against both "Science" and Enlightenment based dogma in general. Philosophers such as Michel Foucault are often understood as arguing that the "age of reason" had to construct a vision of "unreason" equally beingness demonic and subhuman, and therefore evil and befouling, whence by analogy to debate that rationalism in the modern menstruation is, likewise, a construction. Alternatively, the Enlightenment was used as a powerful symbol to argue for the supremacy of rationalism and rationalization, and therefore whatsoever attack on it is connected to despotism and madness, for example in the writings of Gertrude Himmelfarb and Robert Nozick.

This is not to be confused with the role of specific philosophers or individuals from the Enlightenment, simply the utilize of the term in a broad sense past writers in the present of varying points of view.

Precursors of the Enlightenment

- Polish brethren

- Louis Xiv

- Henry Eight

- René Descartes

- Blaise Pascal

- Thomas Hobbes

- Francis Bacon

- Nicolaus Copernicus

- Galileo Galilei

- Algebra

- Analytic Geometry

Important figures of the Enlightenment era

- French Encyclopédistes | Voltaire | Leibniz | Jean-Jacques Rousseau | Condorcet | Helvétius | Fontenelle | Olympe de Gouges | Ignacy Krasicki | Francois Quesney | Benedict Spinoza | Cesare Beccaria | Adam Smith | Isaac Newton | John Wilkes | Antoine Lavoisier | Grand.Fifty. Buffon | Mikhail Lomonosov | Mikhailo Shcherbatov | Ekaterina Dashkova

- Jean le Rond d'Alembert (1717-1783) French. Mathematician and physicist, ane of the editors of Encyclopédie

- Thomas Abbt (1738-1766) German. Promoted what would later be chosen Nationalism in Om Tode für'south Vaterland (On dying for 1's nation).

- Pierre Bayle (1647-1706) French. Literary critic known for Nouvelles de la république des lettres and Dictionnaire historique et critique.

- James Boswell (1740-1795) Scottish. Biographer of Samuel Johnson, helped established the norms for writing Biography in general.

- Edmund Burke (1729-1797) Irish. Parliamentarian and political philosopher, all-time known for pragmatism, considered important to both liberal and conservative thinking.

- Denis Diderot (1713-1784) French. Founder of the Encyclopédie, speculated on free will and zipper to material objects, contributed to the theory of literature.

- Ignacy Krasicki (1735-1801)Polish. Outstanding poet of the Smooth Enlightenment, hailed by contemporaries as "the Prince of Poets." Subsequently the election of Stanisław August Poniatowski as rex of Poland in 1764, Krasicki became the new King'due south confidant and chaplain. He participated in the King's famous "Thursday dinners" and co-founded the Monitor, the preeminent periodical of the Shine Enlightenment, sponsored by the King. Consecrated Bishop of Warmia in 1766, Krasicki thereby also became an ex-officio Senator of the Polish-Lithuanian Republic.

- Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790) American. Statesman, scientist, political philosopher, author. As a philosopher known for his writings on nationality, economic matters, aphorisms published in Poor Richard'south Alamanac and polemics in favor of American Independence. Involved with writing the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of 1787.

- Edward Gibbon (1737-1794) English. Historian best known for his Decline and Autumn of the Roman Empire.

- Johann Gottfried von Herder German. Theologian and Linguist. Proposed that language determines idea, introduced concepts of ethnic study and nationalism, influential on later on Romantic thinkers. Early on supporter of democracy and republican self rule.

- David Hume Scottish. Historian, philosopher and economist. Best known for his empiricism and skepticism, advanced doctrines of naturalism and material causes. Influenced Kant and Adam Smith.

- Immanuel Kant German language. Philosopher and physicist. Established critical philosophy on a systematic basis, proposed a material theory for the origin of the solar system, wrote on ethics and morals. Influenced by Hume and Isaac Newton. Important figure in German Idealism, and important to the work of Fichte and Hegel.

- Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) American Statesman, political philosopher, educator. As a philosopher best known for the Declaration of Independence and his estimation of the Constitution which he pursued as president. Argued for natural rights as the basis of all states, argued that violation of these rights negates the contract which bind a people to their rulers and that therefore at that place is an inherent "Right to Revolution."

- Hugo Kołłątaj (1750-1812) Polish. He was active in the Commission for National Education and the Society for Elementary Textbooks, and reformed the Kraków Academy, of which he was rector in 1783-1786. An organizer of the townspeople's motion, in 1789 he edited a memorial from the cities. He co-authored the Shine Constitution of May three, 1791, and founded the Associates of Friends of the Regime Constitution to assist in the certificate's implementation. In 1791-1792 he served as Crown Vice Chancellor. In 1794 he took part in the Kościuszko Uprising, co-authoring its Uprising Act (March 24, 1794) and Połaniec Manifesto (May 7, 1794), heading the Supreme National Council's Treasury Department, and backing the Uprising's left, Jacobin wing.

- Gotthold Ephraim Lessing (1729-1781) German Dramatist, critic, political philosopher. Created theatre in the German, began reappraisal of Shakespeare to being a fundamental figure, and the importance of classical dramatic norms equally being crucial to expert dramatic writing, theorized that the eye of political and cultural life is the center class.

- John Locke (1632-1704) English language Philosopher. Important empricist who expanded and extended the piece of work of Francis Bacon and Thomas Hobbes. Seminal thinker in the realm of the relationship betwixt the state and the private, the contractual ground of the country and the rule of law. Argued for personal liberty with respect to property

- Leandro Fernández de Moratín (1760-1828) Spanish. Dramatist and translator, support of republicanism and gratis thinking. Transitional figure to Romanticism.

- Montesquieu

- Nikolay Novikov (1744-1818) Russian. Philanthropist and journalist who sought to raise the culture of Russian readers and publicly argued with the Empress.

- Thomas Paine (1737-1809) American. Pamphleteer and polemicist, most famous for Common Sense attacking England's domination of the colonies in America.

External links

- Dictionary of the History of Ideas: The Enlightenment

- Dictionary of the History of Ideas: The Counter-Enlightenment

- [1] Introduction to the Enlightenment

References

- Jonathan Loma, Faith in the Age of Reason, Panthera leo/Intervarsity Press 2004

- Ernst Cassirer, The Philosophy of the Enlightenment, Princeton University Press 1979

- Marker Hulluing Autocritique of Enlightenment: Rousseau and the Philosophes 1994

- Gay, Peter. The Enlightenment: An Estimation. New York: W. Westward. Norton & Company, 1996

- Redkop, Benjamin, The Enlightenment and Community, 1999

- Melamed, Yitzhak Y, Salomon Maimon and the Rise of Spinozism in German Idealism, Journal of the History of Philosophy, Volume 42, Outcome 1

- Porter, Roy The Enlightenment 1999

- Jacob, Margaret Enlightenment: A Brief History with Documents 2000

- Thomas Munck Enlightenment: A Comparative Social History, 1721-1794

- Arthur Herman How the Scots Invented the Mod Globe: The True Story of how Western Europe's Poorest Nation Created Our Globe and Everything in It 2001

- Stuart Brown ed., British Philosophy in the Age of Enlightenment 2002

- Alan Charles Kors, ed. Encyclopedia of the Enlightenment. 4 volumes. Oxford: Oxford Academy Press, 2003

- Buchan, James Crowded with Genius: The Scottish Enlightenment: Edinburgh'southward Moment of the Listen 2003

- Louis Dupre The Enlightenment & the Intellctural Foundations of Modern Culture 2004

- Himmelfarb, Gertrude The Roads to Modernity: The British, French, and American Enlightenments, 2004 im Ganster ( :

- Stephen Eric Bronner Interpreting the Enlightenment: Metaphysics, Critique, and Politics, 2004

- Stephen Eric Bronner The Great Divide: The Enlightenment and its Critics

- Henry F. May The Enlightenment in America (New York: Oxford Academy Printing, 1976)

Source: https://psychology.fandom.com/wiki/The_Age_of_Enlightenment

0 Response to "What was the Age of Enlightenment/ Age of Reason and what led to this shift in thought"

Post a Comment